Class News

We're Not Destroying Rights, We're Protecting

Parade Magazine

May 19, 2002

When he has a spare moment, which is rare nowadays. U.S. Attorney General John Ashcroft likes to duck into a little storage room next to his office. There, seated in front of a window that affords a spectacular view of the Capitol, he takes his electronic keyboard and accompanies himself as he sings blues, jazz, pop classics and gospel hymns:

Keep me true, Lord Jesus, keep me true.

There's a race that I must run,

There are victories to be won.

Give me power every hour to be true.

A devout Pentecostal, Ashcroft does not presume to say whether his prayers have been answered from on high. But there is no doubt that he has emerged, in the aftermath of Sept. 11. as the most powerful Attorney General since Robert F. Kennedy four decades ago.

As the nation's chief law-enforcement officer, Ashcroft is in charge of a vast array of powerful agencies, including the FBI, the Drug Enforcement Administration, the Bureau of Prisons, and the Immigration and Naturalization Service. He did not hesitate to use his overwhelming authority to respond to Sept. 11 with a series of bold measures. Among them:

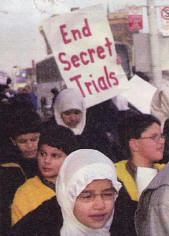

- Supporting secret military tribunals to try suspected aI-Qaeda and other terrorists.

- Tracking down 8000 young Muslim men in America for questioning.

- Detaining hundreds of people on immigration violations without releasing their names or whereabouts.

- Giving the Justice Department the authority to overrule immigration judges.

- Permitting federal officials to listen in on hitherto privileged conversations between certain prisoners and their attorneys.

Though many of Ashcroft's policies are wartime measures, they have raised troubling questions for the long run: Just how far is the Bush Administration prepared to push the Constitutional envelope? Do Ashcroft's actions threaten to concentrate too much power in the Executive Branch of government? In pursuit of national security, are we sacrificing the very rights we say we are fighting for?

In search of answers, I spoke with U.S. Representatives, Senators, and Constitutional scholars, and had an hour-long conversation with Ashcroft in his temporary quarters in the Main Justice Building.

"My job is to disrupt. curtail, destabilize, delay, and prevent terrorism." Ashcroft told me. "And I'm going to do everything I can think of that's within the limits of the charter of freedom we call our Constitution."

It is precisely on this matter of our "charter of freedom" that the Attorney General has been chastised by civil libertarians of all political stripes, ranging from Patrick Leahy, the liberal chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, to Bob Barr, the conservative Representative from Georgia.

"If we get accustomed to a system of detention and surveillance," Harvard's Laurence Tribe, a renowned Constitutional lawyer, told me, "we may wake up and find to our dismay that we live in a state that has sold far more of its liberty in exchange for its security than it would do willingly.'

Given the widespread fear of another terrorist strike, it is hardly surprising that Ashcroft's tough tactics have won the support of more than two-thirds of his fellow citizens, according to the latest polls. However, his personal popularity in Washington is another matter. He has raised political hackles in Congress because of his reluctance to consult its members before he acts or to accept any checks on his role as the general in charge of the domestic war on terrorism. As a result, Ashcroft has become perhaps the most controversial figure in the Bush Administration, the man the President has called his "lightning rod."

The Attorney General's small office is decorated with sports memorabilia from his home state of Missouri ― a baseball bat collection and a replica of the St. Louis Rams' 2000 Super Bowl trophy. There also is a framed photograph of his friend Barbara Olson, wife of Solicitor General Theodore Olson, who lost her life on the hijacked jetliner that was crashed into the Pentagon.

Ashcroft ― married, with three grown children ― is a tall, slightly overweight man of 60 who dresses every day in a starched white shirt, polished black shoes, and dark suit. The son and grandson of fundamentalist Christian preachers, he grew up in a Springfield, MO, household where smoking, drinking, and dancing were forbidden. His only known lapse into temptation stems from a sweet tooth: He eats a hot-fudge sundae every day.

One of Ashcroft's innocent pleasures is singing. As a Senator, he performed with colleagues Trent Lott of Mississippi, Larry Craig of Idaho, and Jim Jeffords of Vermont in a barbershop quartet called The Singing Senators. "The group, it is fair to say, has fallen into disbandment," Ashcroft quipped. "I haven't had time to sing."

After graduating from Yale and the University of Chicago Law School, Ashcroft was elected Missouri's attorney general in 1976 and built a reputation for opposing court-ordered plans for school desegregation in St. Louis and Kansas City. Later, as a two-term governor and then U.S. Senator, he won the gratitude and support of conservative Republicans nationwide by advocating that the Constitution be amended to allow school prayer and to outlaw abortion and flag burning.

Ashcroft was endorsed by prominent members of the Christian right as a candidate for President in 2000 until he decided to seek re-election to the Senate, a race he ultimately lost to Mel Carnahan, who had been killed in a plane crash during the campaign. (Carnahan's widow, Jean, was appointed to take his seat.)

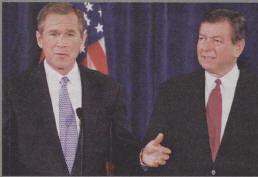

After the election, President Bush named Ashcroft to be his Attorney General in an effort to solidify the Administration's right-wing base. The nominee was known as a fierce partisan who had chalked up a record as one of the most conservative members of the Senate, and his former colleagues gave him a hard time during his grueling confirmation process.

It did not help Ashcroft's cause that he had once given an interview to the Southern Partisan, a periodical often described as the voice of the neo-Confederacy, and had told an audience at Bob Jones University, "We have no king but Jesus." Ultimately, he won Senate confirmation by a 58 to 42 vote ― the most votes against a U.S. Attorney General in history.

To this day, his detractors believe Ashcroft is a zealot on a moral crusade. After less than a year in office, his aide concealed a bare-breasted statue in the Justice Department's Great Hall with a blue curtain, leading some in Washington to refer to the covering as a "blue burkha" and to the Attorney General as "Mullah Ashcroft."

The Attorney General's unwavering religious conviction and espousal of moral rectitude, while making him an easy target for criticism, seem sincere and deeply felt. I asked Ashcroft if he ever had experienced a moment of crisis in his Christian faith. "There were times when I had to make a decision that this was the way in which I wanted to go," he said. "It happened pretty early in my life. I made some pretty clear decisions [about my faith] when I was 12 years old, but I've had to reaffirm those decisions on numerous occasions."

His sense of righteousness has gotten him into trouble in the political arena. Ashcroft ran into a fusillade of disapproval for suggesting in a post-Sep. 11 hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee that his critics were treading close to treason. To those who scare peace-loving people with phantoms of lost liberty," he said, "my message is this:

"Your tactics only aid terrorists, for they erode our national unity and diminish our resolve. They give ammunition to America's enemies and pause to America's friends."

I asked if he regretted making that statement, which has been characterized as inflammatory. "I haven't given it a second thought." Ashcroft replied.

"Why are some of your harshest critics conservatives, like Bob Barr and columnist William Safire?" I asked.

"People misunderstand what we're doing," he said. "Headlines saying that I'm listening in and eavesdropping on lawyer-client conferences are misleading. We're only doing that when it is necessary to stop violent activity."

At times, Ashcroft has displayed a degree of flexibility. After Sept. 11, he was accused of showboating in front of the TV cameras, stealing the spotlight from the FBI's new director, Robert Mueller III. Since then, in response to criticism, Ashcroft has taken a somewhat less public role.

The Administration also has modified its controversial position on military tribunals. Suspected terrorists now will have the right to an appeal and ― with major national security exceptions ― to have their trials conducted in public.

Even his opponents concede that Ashcroft's record has to be judged in the light of history. By that standard, the Attorney General has not proposed anything as extreme as the 1798 Alien and Sedition Acts, the suspension of habeas corpus during the Civil War, or the internment of 120,000 Japanese-Americans under Franklin Roosevelt.

Some of the people I spoke with believe that Ashcroft dreams of becoming President someday and has been taking advantage of the war on terrorism to promote his political agenda. His name is mentioned prominently in Republican circles as a possible running mate for President Bush in 2004 if Vice President Dick Cheney decides to step aside for health reasons.

Sometimes it seems that people object more to Ashcroft's manner than to the substance of his policies. For instance. Ashcroft deeply offended Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Leahy by failing to respond to his letters raising questions about detention and military tribunals ― a lapse Leahy blamed on political operatives in the White House.

"John Ashcroft has been given his marching orders by the White House and is doing his best to carry them out," Leahy said. "He is not an independent Attorney General. Every Attorney General has to decide what kind of AG he wants to be, and Ashcroft has decided to be the White House point man."

Said Floyd Abrams, a noted First Amendment lawyer: "There are people like me who are prepared to give quite a lot in the area of privacy ― having cameras film us, having people listen to our telephone calls ― because we think the risks to our country are so grave. But part of the problem with Ashcroft is that he is tone-deaf to civil-liberty issues, so he often makes the worst case, instead of the best, for what he wants to do and loses some support he might otherwise have."

I asked Ashcroft how he would respond to those who say that his policies have jeopardized the very liberties we are fighting for.

"The security we are fighting for is not security for nothing," he said. "We're not destroying rights. We're protecting rights. I believe the American people deserve to have their rights protected, and that is the job of the Justice Department."