Class News

Angus Gillespie '64 and the Holland and Lincoln Tunnels

The New York Times article below, on the Holland and Lincoln Tunnels, focuses on an exhibit at the Hoboken Historical Museum, which used Angus Gillespie's book Crossing Under the Hudson — among others — as a template for the exhibit. Buy the book on the Publications page.

When a Road Opened Under the Hudson

New York Times

March 2, 2012

A re-creation of the New York and New Jersey state lines

at the Hoboken Historical Museum

Late one November evening in 1927, the cars trying to get into the Holland Tunnel were pressed up against the eastbound entrance — a vehicular scrum, moving nowhere — when their drivers began to communicate in what has since become the customary language of that dense, acrid patch of Jersey City. They began to honk their horns.

What moved them to honk then, though, was not what moves drivers to honk now. It wasn't the other side of the tunnel they were impatient to reach, but the inside of the tunnel itself. A miraculous thing was about to happen — the opening of a road beneath the Hudson River — and their honking was a chorus of excitement.

"It's clear a lot of people absolutely hate the Holland Tunnel now, but at the time it opened they thought it was wonderful," said Robert W. Jackson, author of a recently published history of it, Highway Under the Hudson, which recounts that evening in 1927. "They were enchanted by the whole idea that you could actually drive under water."

An attempt to recapture some of that enchantment — a word not much used in conjunction with subaqueous motoring these days — is on display through July 1 in Hoboken, the dense city bracketed north and south by two unseen and mostly unloved feats of civil engineering: the Lincoln and Holland tunnels, through which 76 million vehicles travel each year, few of them honking for joy.

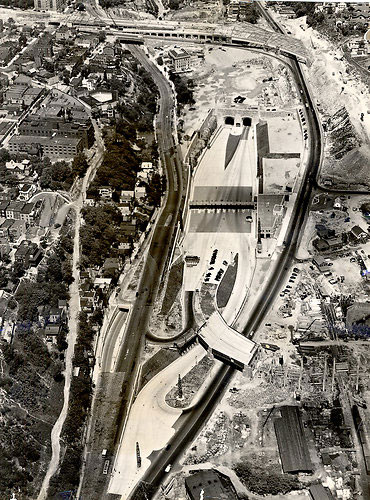

An aerial view of the construction around the Lincoln Tunnel

in May 1938, 6 months after the tunnel opened.

"You take them for granted because you just drive into them and then you're in and out in minutes, and it's purely a functional thing," said David Webster, collections manager at the Hoboken Historical Museum, who helped assemble the exhibition here, "Driving Under the Hudson: A History of the Holland and Lincoln Tunnels." "One of the things we've tried to introduce is an appreciation for the tunnels as something more," he added.

The museum occupies a portion of the old machine shop of the defunct Bethlehem Steel shipyard, a long brick building looking out across the piers toward the Manhattan skyline, which looms so tantalizingly close as to have tempted generations of politicians, financiers, transportation moguls, and engineers to concoct faster ways to reach it. The narrow, high-ceilinged exhibition space is filled with photographs, documents and artifacts — like old toll receipts and souvenir tin toys — chronicling the epic story of crossing under that last mile-and-a-quarter barrier between New York City and the rest of America.

The exhibition is chronological, and the early years are a story of big dreams and failed schemes for replacing the ferries and railroad barges that got people and goods across the Hudson until the early 20th century. On display here is the 1895 cornerstone for the proposed North River Bridge, and a rendering of what might have been: a fearsome-looking rail span, 14 tracks wide, that would have left a broad swath of Hoboken in perpetual shadow.

The first tunnels for passenger trains under the river opened in 1908, but then came another problem: how to accommodate all the new motor vehicles that were beginning to fill the roads. A bridge seemed the most logical answer, but was also, at an estimated $42 million, the most costly. A tunnel would be far cheaper, $11 million, and would gobble much less land, but would also be more difficult to engineer.

Planning dawdled until the arctic winter of 1917-18, when the Hudson froze and coal was stranded on the New Jersey docks while New Yorkers shivered. The ice eventually melted, and so did opposition. After much political wrangling, New York and New Jersey managed to reach an agreement, choose as the chief engineer the young Clifford M. Holland — whose plan for two tubes won out over the single-tube plan promoted by the venerable George Washington Goethals, builder of the Panama Canal — and start digging.

"If they had not figured out a way to handle the ventilation system," Dr. Jackson said, referring to the method of dealing with the exhaust fumes from motor vehicles, "the tunnel wouldn't have worked, and prior to the Holland Tunnel they had not figured that out."

Four tall ventilation towers circulate air under the roadways and back out, keeping it cleaner in the tunnel, as measured by tests at the time, than in Midtown Manhattan — a solution devised by Ole Singstad, who went on to design several other tunnels, including the Lincoln. "The solution was so elegant and perfect that it's been copied in virtually every vehicular tunnel built since," said Dr. Jackson, an urban planner from Texas who holds a Ph.D. in American civilization and has written widely on the history of engineering projects in the United States.

Construction of the tunnel cost at least 13 lives; a 14th was the chronically stressed and overworked Mr. Holland himself, who died just two days before the eastward tunneling crew and the westward tunneling crew met beneath the river for the momentous "hole through" in 1924. "It did wear on him, and unfortunately drove him to his grave," Mr. Webster said.

His tunnel was quickly named for him. "It's extremely unusual to have a work of heroic civil engineering named after the engineer," said Angus Kress Gillespie, a professor of American studies at Rutgers University whose recent book Crossing Under the Hudson recounts the history of both the Holland and Lincoln Tunnels and was, along with Dr. Jackson's book, a source of both inspiration and information for the Hoboken exhibition. Dr. Gillespie is scheduled to give a talk at the museum on March 4 at 4 p.m.

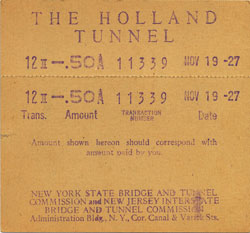

A toll receipt from 1927.

The fee for cars was 50 cents.

The toll was 50 cents when it opened, and the old traffic graphs hanging in the exhibition show that it was an immediate hit, soon carrying 35 million vehicles a year. Plans were quickly made for another tunnel, which was originally known as the Midtown Holland Tunnel.

"The way I kind of see it is that the Lincoln Tunnel is the son of Holland," Dr. Gillespie said. "It's kind of frightening, the thought of going underneath the river, and the powers that be were afraid that people wouldn't accept it."

Because the Holland had solved the engineering problems of a vehicular tunnel, the new tunnel, it was thought, would be easier to build. But what the Holland had not solved were the financial problems. The first tube of the Lincoln Tunnel opened in 1937; the third did not open until 20 years later.

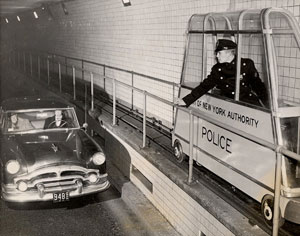

A catwalk car carried police officers in a test

above the Holland Tunnel's traffic in 1954.

One of the cars is in the exhibition.

Near the end of the exhibition in Hoboken is its prize artifact: one of the narrow electric cars that used to carry police officers along the catwalk that borders the roadway in the Holland Tunnel. The catwalk car was the fastest, surest way through the tunnel, gliding blithely past the most epic traffic jams — equipped with no horn, because none was needed — but, alas, it was taken out of service last spring.

"Driving Under the Hudson: A History of the Holland and Lincoln Tunnels" is at the Hoboken Historical Museum, 1301 Hudson Street, through July 1. Information: hobokenmuseum.org; (201) 656-2240.