Class News

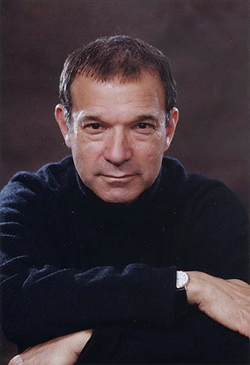

Stephen Greenblatt '64 interviewed on Adam and Eve

Here is an interview with Pulitzer Prize-winning scholar Stephen Greenblatt by the Harvard Gazette on the subject of his book The Rise and Fall of Adam and Eve, published by Norton in 2017. The interview was published on October 24, 2017.

Listen to the interview and/or read an excerpt below.

Eden as a storyteller’s paradise

John Cogan University Professor of the Humanities Stephen Greenblatt opens his new book, “The Rise and Fall of Adam and Eve,” by recalling a pivotal moment from his Roxbury childhood. Attending synagogue on the Sabbath, he is told by his parents to keep his eyes closed for final prayers to allow God to pass overhead, for anyone who sees God face-to-face will die. But the young Greenblatt tests the warning, opening his eyes to find no otherworldly spirit. It was only a story, he realizes — and now he’s hooked for life.

“We surround ourselves with them; we make them up in our sleep; we tell them to our children; we pay to have them told to us. Some of us create them professionally. And a few of us — myself included — spend our entire adult life trying to understand their beauty, power, and influence,” he writes.

Greenblatt, a Shakespearean and literary historian who won a Pulitzer Prize for “The Swerve: How the World Became Modern,” follows the centuries-long saga of Adam and Eve across academic disciplines ranging from the artistic to the theological, enriching “Rise and Fall” via cameos by Harvard colleagues David Damrosch, David Pilbeam, Janet Browne, and Edward O. Wilson. In a Gazette Q&A, he talked about the course that inspired the book, the shadow of Milton, and the animals that guided him to a moment of profound perspective.

GAZETTE: How long have you wanted to tell this story?

Dean Robin Kelsey (left) chats with Stephen Greenblatt

about Greenblatt's new book "The Rise and Fall of Adam

and Eve,"about the reach, growth, and power

of the Bible story.

GREENBLATT: My first email about it goes back to 2013, but I was thinking about it well before that. The book was about five years in the making, but I had already taught a set of courses on the subject at Harvard with Joseph Koerner [the Victor S. Thomas Professor of the History of Art and Architecture], so I was interested already. Teaching and writing often go hand in hand. We originally taught it as a graduate course, later as an ethical reasoning general education course. The book originated in some sense in the course.

The story of Adam and Eve touches almost everything. It’s literature and art, painting and sculpture, theology and philosophy and biology. It made research both fun and difficult. I’ve shuttled back and forth in my life, between thinking about things over which I have some nominal control (Shakespeare) and things over which I have no claim to possession (this story is a perfect example). I love the challenge of getting some grip on what I know that I will never fully master. One could spend five or 50 years and not get close to exhausting this particular subject.

GAZETTE: Why did you feel it needed to be told to a wider audience?

GREENBLATT: I’m interested in the power of the humanities and the power of storytelling literature. I think they matter more than ever, yet we are grappling with a widespread assumption that they count for very little. The fate of Adam and Eve in the Garden is arguably the single most powerful and influential story in the Western world. It’s a great place to go to ask why stories work and how they are transmitted. On the one hand, you get hundreds of thousands of people who are touched by it and pass it on, and, on the other hand, you get a very small number of extraordinary people who don’t simply pass it along but who change it, transform it. Some of these — Augustine, Dürer, Milton — figure in my book.

GAZETTE: You write about an Italian nun, Arcangela Tarabotti, who published in the mid-1600s an indictment of the use of the Adam and Eve story to condemn women. Is the cultural history of the story a history of misogyny?

GREENBLATT: Yes, in many ways it is, but it was not always and necessarily so. Among the very earliest traces discovered in 1946 in Nag Hammadi is an ancient book that proposed that Eve is the hero of the story because she chose knowledge over ignorance. And even if this interpretation hardly prevailed, it is interesting that the biblical narrative thought that the male domination of women needed an explanation: It was evidently not natural. In modern times there are many powerful feminist discussions, but they pick up details that were noticed long ago. The story is like a bone caught in the throat — you can’t cough it up and you can’t swallow it down.

GAZETTE: You devote several chapters to Milton. Does the way the modern world thinks about Adam and Eve really come down to his less-than-ideal marital relations?

GREENBLATT: More than anyone else, Milton gave Adam and Eve the intimate life of a married couple, a couple who eat together, entertain guests, share dreams, make love, work through uncomfortable disagreements. Of course the poet brought to this remarkable creative task his own experience of marriage, its pains as well as its pleasures. The people who’ve changed the story threw themselves into it, body and soul. They held nothing back. The account I give in my book of Milton’s life isn’t decorative background. It’s of the essence.

GAZETTE: You describe the book’s moving end — in Africa where you visited the Kibale Chimpanzee Project — as the closest to paradise you will get. What made it so unforgettable?

GREENBLATT: I was fortunate to get permission to visit the research station in western Uganda directed by Richard Wrangham, who teaches evolutionary biology at Harvard. It was one of the great, thrilling experiences of my life. I wanted to see what our own origin account actually looks like, as it were, in the flesh. It is thought that the creatures from whom our own species emerged most closely resembled modern-day chimpanzees; the revelation for me is that chimpanzees as far as we can tell live without. In the forests we see beings who are strikingly like ourselves but who, as far as we can tell, live without awareness of death, without knowledge of good and evil, without shame. That is, we witness in a strange form much of what the ancient story imagined as the lives of the first humans in Eden. It’s a remarkable sight — moving and unsettling.