Class News

Dick duPont ’64 tells about his only aircraft accident in 50 years of flying

February 22, 2024

Dick duPont ’64 offers the following story about his only aircraft accident in 50 years of flying.

A Wintry Day in Iowa

by Dick duPont

Those recent frigid Caucuses remind me I still owe Taft and Yale classmate Pat Caviness the story of my only aircraft accident in fifty years of flying. I was just a passenger, but I was a pilot too by then. I hope that perspective helps me better relate the details of this mishap. And please don’t let the caucus bit mislead you. This short piece is definitely apolitical. It’s just that whenever someone mentions Iowa, the first thing that comes to my mind is our engine failure.

Osceola

The accident took place just after take-off at Osceola, Iowa — from a grass strip — in my cousin Lex’s single-engine Cessna 185 (N9802X). It was January 1962. The weather was not nearly so cold as this year’s events — just a typical Iowa winter day with a high of plus 15 degrees F — but the wind was gusting to 35 kts in blustery post-frontal conditions. So that part, with its sub-zero wind chills, brought ice to the mustache, if you fancied one. Our cleanshaven crew, Lex duPont, Ray Lloyd and I, were spared all that, but to little avail considering what lay ahead for us. Now I could dispense with my tale in just a few sentences, but that wouldn’t be much fun. So let me say something about my cousin Lex, then explain what we were doing out in Osceola in the first place.

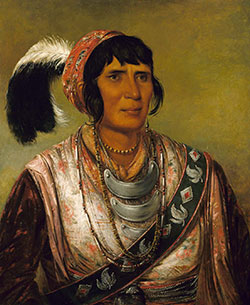

Thirteen years my senior, Lex was the true hero of this episode. Very much like his father, E. Paul duPont — a man of first-rate engineering talent who accomplished a great deal throughout his life (development, production, and sales of the Du Pont Car for one), I think Lex was the finest hands-on engineer of all E. Paul’s sons. Lex was passionate about his calling — the only fellow I ever knew who carried a miniature crescent wrench on his key chain. I came to know Lex as my cousin who kept his WW ll Grumman Wildcat in one of our cousin Kip’s T-Hangars at Summit Aviation (where I took my first flying lessons). He was also the guy next door who still worked in his mother's garage when this story took place.

As an aside, one time Lex took an Amal carburetor off one of his Norton engines, welded a lobe on the live axle of his Go Kart, fastened a Plymouth fuel pump to that — then ran a fuel line up to the “loaner Amal.” Literally, heaps of alcohol, nitromethane, and castor oil were combined, then forced into his poor little McCulloch engine. To top it off, Lex dyed his fuel concoction a bright green. On race day, he pulled an “Al Stout” and surprised us all with a complete thrashing on the first heat. Lex howled with laughter, until the second heat saw his engine explode on the back stretch at 14,000 rpm — and that was that. Unperturbed, he was so chuffed over the first heat he couldn’t have cared less. Lex never bragged (period), but if asked, he might well have responded: “Don’t mess around with an innovator — he’s liable to drop a jalapeno in your martini.”

Lex’s aviation interests were no less extraordinary. He bought a distressed old Stinson L-5 observation plane and got Ray Lloyd to weld its maze of structural members. At the same time, our resident WWII veteran, Horace “Smitty” Smith, who served in the Burma Theatre keeping our tired C-46’s “fit” for “flying the hump,” was now running Summit’s Maintenance Hangar. He was rebuilding a WW II Ryan PT-22 trainer on the side. That project was going well, until it became clear he needed to look for a better wing assembly. Lex located just what Smitty needed. All that remained was to fly out to Osceola and close the deal. Enter Ray Lloyd and me.

We left the Pilot-In-Command duties to Lex. O2X was his baby and we were happy just to go along for the ride. Our bags were lightly packed, but we were long on down jackets, boots, gloves, wool neckbands, and hats that would have sold for $1,000 at Donner Pass. You soon learn to pack your plane with what you might need in case of the unexpected — particularly in a single engine aircraft. It was cold enough in Delaware, let alone on the Northern Great Plains.

You know, the nose of a flying fish couldn’t knock a loose barnacle off a humpback, but watch out for the flipside. The same holds for aircraft. Turbulence you may barely notice in a 747 will be akin to the ride of the week in rodeo country — when you’re in a small single-engine plane. As we were landing on the airport at Osceola, the latter was very much the case. We viewed that as annoying — sometimes challenging — but definitely manageable. It was “rough as a cob” on final with a thirty-degree crosswind from the left. Lex “crabbed” his way down the last 500 feet, then kicked the plane straight with the rudders for the flare. When it’s gusty like that, the aircraft doesn’t want to quit flying. You just need to stay with it as you would with an untrained pup on a leash. With a tail-wheel aircraft, landing is a bit more challenging than with a nose-wheel type. Lex was an excellent pilot and handled 02X well, but he was glad when we landed.

We taxied right up to the two lonely weathered gas pumps (80/87 octane and 100/130 octane). We needed to take on fuel at either Des Moines or Osceola. We chose the latter, for two good reasons: the operator appreciated the business in the dead of winter, and he was the chap with the goods Lex came for. It was an Eddie Bauer day for sure, so we accepted his offer of a ride up. Once inside the unheated hangar, I stood back to let Lex and Ray do their thing. I mused, “Where else do you suppose a nearly mint set of PT-22 wings would be stuffed among the rafters of a gnarly little hanger?” In truth, that hangar would have been far more at home next to a vintage sod house on the prairie.

Lex and the airport operator hit it off right away. It was obvious the wing was in very good condition and Lex’s check was equally desirable. In thirty minutes, they shook hands and the transaction closed. They even agreed on what trucker to use. So, no sooner did we land, than off we went again. That actually was a good thing, as we wanted to get checked into to our motel in Des Moines before dark. We thanked a couple of other people in the hangar who helped get the wings down for us, then rode back to the plane and started the refueling. 02X had a cargo pod hung between the fixed landing gear, fastened to the belly. Wisely, Lex had bought the optional extra fuel tank (installed within the pod). It came in handy for his travels, especially longer flights like the one we were about to start. It also saved our ass that day.

The operator made good use of his gloves. Between the biting wind, his ladder, and the frozen aluminum fuel nozzle, his was not a pleasant task. Lex performed the preflight inspection, leaving the wing tie-downs in place for a bit. He “stuck” each tank’s sump drain with a clear plastic sampler to check for fuel color and contaminants — like sediment and water. We were all “cold as Billy-Be-Damned” as Cita (mother) used to say, but we stuck with it and got the job done. Lex signed the fuel chit, rechecked the fuel tank caps, untied the tie-down, and hopped aboard. He bade goodbye to the operator, who waved back and sped up to the warm hangar office. Lex got the engine going straight away, and we all rooted for the heater to do its thing.

Weather conditions for take-off were the same as when we landed earlier. Lex manipulated the flight controls during taxi to keep the wind from playing games with us, but it was still a handful. I was in the copilot’s seat and Ray was in the left rear passenger seat directly behind Lex. Arriving at the departure end of the grass runway, Lex spun 02X straight into the wind, set the brakes and gave the flight controls to me to hold us steady while he performed the engine run-up and take-off check. Holding onto the control wheel was like holding onto the leader wire of a fresh-caught bluefish. The wind pulled and jerked on the control surfaces with every gust. Lex completed his checklist and took back the controls.

When the wind is nasty like that, you want to forcefully take hold of the controls and bloody well make the plane behave. The tail will rise almost instantly as you smartly apply full throttle, Acceleration is immediate. You begin with full aileron deflection into the wind — to keep the upwind wing down where it belongs. As your speed increases, you gradually reduce that input. With a “tail-dragger” you keep extra forward pressure on the elevator and let the tail rise much higher than usual, keeping the main gear in firm contact the runway until you’re well past normal lift-off speed. Then you quickly “pop” the aircraft into the air, “crab” a bit into the wind, and climb out at a good 10-20 kts above normal climb speed — “for Grandma,” so to speak.

Well, our heater finally won. The cabin temperature was increasing nicely. However, we needed to wait a bit more for the oil temperature to rise to within limits. Ten minutes later we had done all there was to do. Lex grabbed the mike and announced our intentions to depart Oceola (in case someone else was damned fool enough to pick that day for flying in). We kept our jackets on for good reason, given the weather conditions outside the cabin. Lex took to the runway, rechecking his fuel selector, mag switches, mixture, and prop controls. Up to this point, everything was just “ducky.” What happened next was not. Here’s the spin.

Up we went — bouncing and shaking in the rough air. The turbulence was moderate — even momentarily severe in the worst gusts. But that all lessened somewhat as we gained a bit of altitude. That said, 02X was a handful nonetheless — so much so that you needed to spend as much time scanning your flight instruments as looking out the windshield. So none of us was gawking at the scenery. We were just passing through 300 feet on runway heading when — Bingo! Our only engine quit running abruptly. Lex first flew the airplane — that’s something you must strive to do no matter what (ask “Sully”). Next, he quickly looked out the windshield and assessed his situation. Seeing nothing but a stoney gulch out front and under us, he ruled out conventional wisdom to proceed straight ahead into the wind and pick the best spot to land. Instead, he turned to the left, bringing into play somewhat lower and better terrain. None of us objected. It wasn’t much, but it bought us perhaps twenty seconds more time. As I looked out the left window, I saw Ray leaning forward to see what he could tell about the cause of the engine failure. I kept scanning outside for more choices. Three hundred feet doesn’t last long in an engineless heavy single-engine plane — not a great glide ratio, already made worse by the turbulence. You can’t be ground-shy and carelessly keep pulling back on the stick or you’ll stall and kill the whole lot on impact. Lex knew that all too well, so he did the only thing he could under the circumstances. He raised the nose gently to give up any excess airspeed, lowering our rate of descent a little. Even so, we just weren’t winning.

Now a hundred feet or so feet above the heavily wooded, hilly terrain, Lex was obliged to roll wings level, accepting what we had — like it or not. I began to scout for the best spot to crash-land. I was just checking the actual trees ahead — in search of two leafy ones, side by side, that might strip off both our wings simultaneously — offering an embrace for our wingless fuselage in their many entwined branches. We all pulled tight our seat belts, and were just about to turn off the fuel, mags, and electric, when a light bulb went off in Lex’s mind. Quickly, he reached over and turned on the emergency fuel boost pump. Instantly the engine started running and Lex applied full throttle. I saw my two leafy trees pass safely under us, unaware of how close they had gotten to the timber mill. Lex continued his now-climbing turn and went straight for the airport, seeking pattern altitude. Because of the strong headwind on climb-out, we had reached 300 feet very close to the departure end of the runway. Then, after turning left, we were abeam and still quite close to the runway. But now the fierce tailwind was sweeping us over the ground like a bloody great tsunami. Then, some ten seconds after restart, our engine quit again with the same abruptness as before. We were at 500 feet — directly over the runway.

We were still too low to execute a “90-270” and land into the wind on the runway. Realizing that, we all shifted gears and looked for a better spot on which to crash land. Good news! All the land across the road on the right side of the runway was a mowed corn field. That would be ever so much better than my famous two trees. In fact, relative to where we were, it was a piece of cake. Lex just needed to lift his left wing ever so slightly and let the booming wind carry us from over the runway to what turned out, on closer inspection, to be three fields of corn fodder separated by barbed wire fencing. We were now down to around 200 feet — almost hovering into the wind like a marsh hawk eyeballing a vole. But we were obliged to get down in a hurry now, for we were already over the middle corn field. Enter another excellent feature.

02X, being #2 off the assembly line, had flaps which were actuated manually via a footlong handle on the floor between the two front seats. It had a release button on the end. Lex rejoiced in his “now you have ‘em, now you don’t” footlong flap handle, but before reaching for that, he switched off the mags, battery, generator, and mixture, then asked me to shut off the fuel selector, which I did. With his left hand on the yoke, Lex used his right hand to press the release button and grabbed “a whole handful of flaps,” pushing the nose smartly down. And down we came — still well within the middle cornfield. As we bottomed out on that maneuver, passing below the tree-line on the right edge of the field, the gusty winds played their mischief and we were robbed of the airspeed Lex needed for a flare. We “plopped” down hard and for real this time. The main gear struts and wheels broke off at impact, reducing our situation to a wheels-up landing.

But here’s the really good news! The cargo pod served to absorb our impact with the corn field. The actual landing was, in all candor, more tolerable than some of my worst landings over the years. However, sliding along in that fashion, it became clear we wouldn’t come to a stop before reaching the barbed-wire fence which separated the two corn fields. Lex had no way to steer 02X in this last phase. As we approached the fence doing perhaps 15-20 mph, we had our final two nice breaks: (1) we contacted the fence exactly between two posts; and (2) the barbed wire had been strung on the far side of each post. We just plowed the barbed wire with our bent propeller until we stopped. We were popping staples left and right. That fence proved to be a first-rate carrier landing device. In summary, there was more discomfort that day from the air turbulence than from the overall crash sequence. What a fine bit of flying Lex delivered. He was the hero of that unexpected mishap for sure. Typical of such, Lex was somewhat disappointed with the outcome and said so. Neither Ray nor I would put up with any such thoughts. You can’t expect perfection. We were delighted with Lex’s performance and said, "Hell, we walked away unscathed and are here to celebrate it. What more could we ask for?"

The cause of the accident was engine failure due to interruption of the fuel supply. The airport fuel tanks were underground at an ambient temperature well above freezing. So was the fuel's temperature, when first pumped. As Lex drained the sumps, the water was still in suspension and difficult to detect. By the time we took off, ice had begun to form in the tanks and fuel lines, ultimately clogging them. The emergency fuel boost pump worked for a short spurt, because its line ran from the cargo pod direct to the engine. Fuel in that bit of line was not yet contaminated, but was sufficient to get us running again, albeit for only a brief time.

Could’ve been us!