Class News

Dick duPont ’64 reflects on flying the Pacific

June 2, 2025

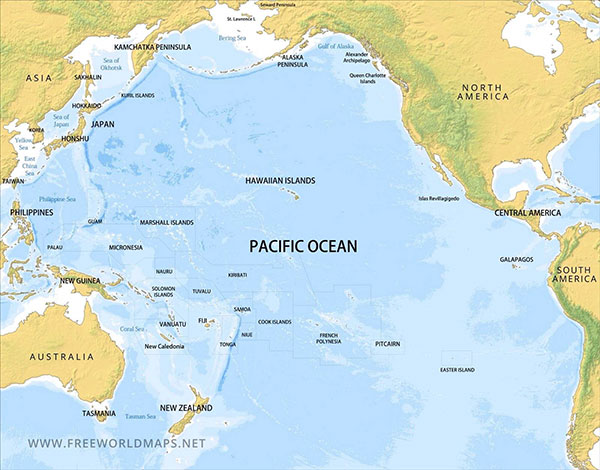

Dick duPont ’64, a lifelong pilot (military, commercial, private) submitted the following essay on the Pacific Ocean from an aviator’s point of view. The Pacific is unimaginably large (64,000,000 square miles) and its islands are tiny (totaling 30,000 square miles). Hence the title of Dick’s essay.

Helluva Lota Blue — Not Much Tan

by Dick duPont

Andersen AFB, Guam

Wake Island

Kwajalein Island

Johnston Island

Clark AFB, Philippines

Looking for Bruce and Zack

These small atolls were a welcome sight when you arrived low on fuel with no other destination anywhere near within range. (Were she alive today, Amelia Earhart could speak convincingly about that.) Of course, you needed to keep a sharp eye out for any weather way before you arrived — in fact prior to the point of no return when a serious commitment has to be made. And you needed to plan your flight to arrive during daylight hours. Fortunately, weather was not a problem in that part of the Pacific at that time of year, but nevertheless, you’ve still got to find those minuscule volcanic nubbins when you get to where you reckon they should be. Even in the late 60’s, we had no GPS, Doppler, inertial guidance systems, or the like. Our navigational equipment was much the same as that which Amelia Earhart’s Lockheed Electra had on board in 1937. Like her, we required a navigator with excellent maps. (I’d venture to guess that our navigator's maps were cut from a better cloth than was her unfortunate chap's.) However, by the time we came along, a whole bunch more people had been crisscrossing our entire globe, so we had a pretty good handle on where things actually are out in the middle of the vast Pacific.

Another point worthy of mention is the size of the runways on these atolls. As you can see, there is only so much real estate available. Moreover, airplanes and their engines do not perform well in hot weather. After we refueled, replenished our supplies, and got some food and sleep, we were once again that same old lumbering piston transport heavily laden with as much fuel as we could cram in her tanks, but now instead of surplus runway at California or Honolulu, we were looking at runway constraints. The margin for error was slim — so much so that it gave birth to a standing tale at Johnston Island of a shark called “Mag-Check Charlie.” He would hang out at the end of the runway listening for any signs of weakness during engine run-up. If he heard a rough-running engine, the place was so small he had plenty of time to mosey on down to the departure end of the runway and await dinner. (An engine failure at lift-off in those conditions was dicey at best. Heavy as we were, we really wanted all four engines running for the first 500 feet of altitude.)

As you would imagine, passengers didn’t gravitate to our flights. That’s why we always carried freight to Vietnam and back-hauled as many bodies as we could to Delaware. (Live passengers got to fly in the turbine equipment). And like the trip out, the trip back was equally monotonous and tiring. So, we would get up and out of the pilot seats one at a time, from time to time, to take a respite. There was a coffee maker in the cargo area. I would get me a coffee each time, but as I did, I never failed to glance down randomly at the labels on the nearest aluminum body boxes. Inevitably I would spend some time musing over the contents ... How young was he when he died? Do you think he's in one piece inside there? What sort of town did he grow up in? Did he have many siblings? How about a girl friend or wife? I wonder if he played sports like we did? I'll bet he did. Of course, his parents would know by now — but, Christ, can you imagine the grief they're feeling?? ... And thus it would go, one box after another. Even today, when our dead soldiers arrive back at that same Dover AFB morgue we helped keep busy, I still pause to scrutinize the TV as the welcoming ceremony is documented yet another time.

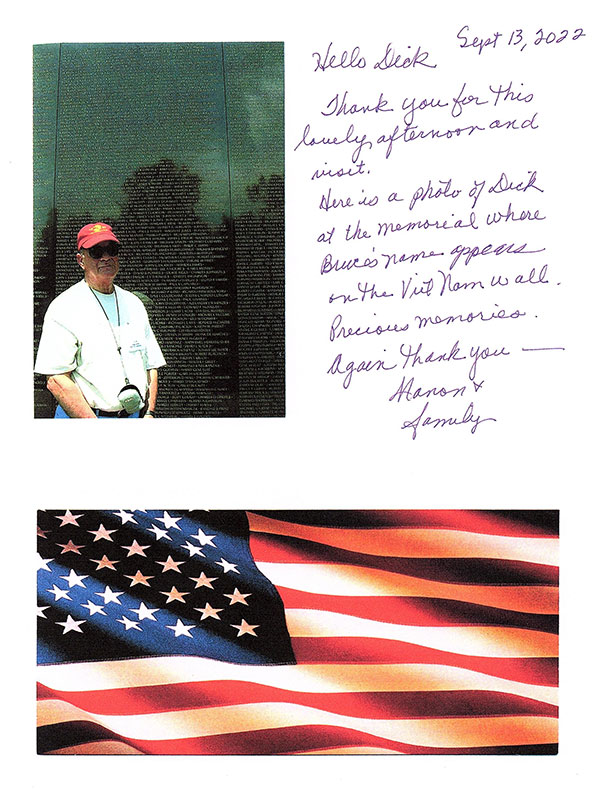

Photo by Elaine Hanowell

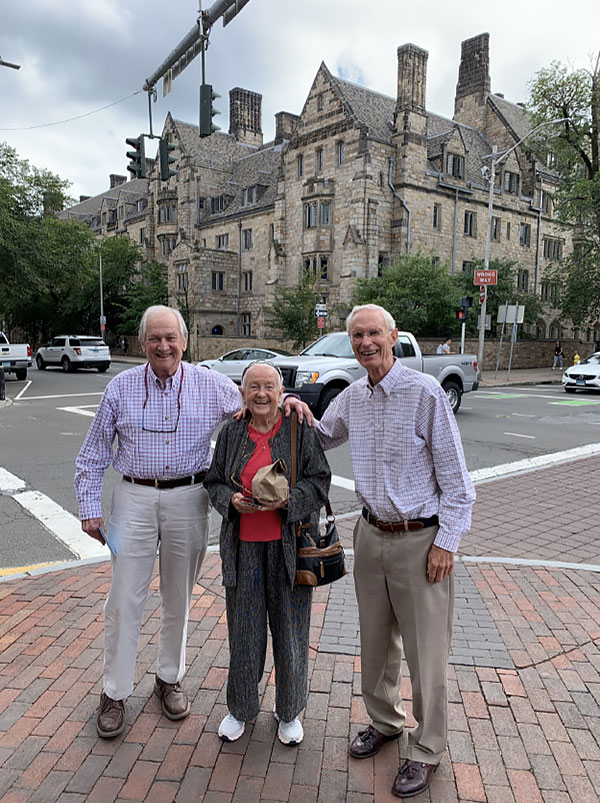

Zack Krieger, my roommate at Taft and Yale, is photographed here on tour of Vietnam, which he took in 2017 with his partner, Elaine Hanowell. Actually, Zack and I go back further than Taft. He was the first childhood Friends School chum invited to my home during our kindergarten year. So that makes Zack my oldest living close friend.

Zack grappled with Vietnam in many ways, including a bout with serious lung cancer a few years ago that was traced back to Agent Orange. (I shudder to think I might have carried that over to Da Nang.) He wrote, “The trip’s most important takeaway for me was seeing how well the Vietnamese have recovered from the war and rebuilt their society.”

Sam:

I flew C-97's with the Delaware Air National Guard 166th Air Transport Wing as Aircraft Commander over world-wide routes — but only once to Vietnam. Later, after eight years part-time service (when I had satisfied my commitment), I resigned and was discharged never having flown a military jet since T-37's and T-38’s in1966 at USAF Flight School at Laredo AFB. Go figure!

duPs

Flying a local training flight just south of Wilmington, Delaware

Author Manon Gagliardi Sam Crocker

[Editor’s note: Manon Gagliardi is the widow of Dick Gagliardi, who coached freshman hockey when Dick played. Gagliardi went on to become head coach of the varsity hockey team. See reminiscences of Dick Gagliardi by Dick duPont.]